Tips & Tricks - Get More out of Wipster

If you're a new user of Wipster or have just missed some of our recent updates, you might have missed some things:--Wipster's suite of integrations...

Spend some time in Facebook groups or forums on filmmaking and video production, and someone will eventually mention the 180-degree shutter rule: “you must use a 180-degree shutter to get natural-looking, cinematic motion blur”.

If you question the rule you’re quickly labeled an amateur. But the 180-degree shutter rule is a myth!

Motion blur in film and video is always determined by shutter speed (Exposure Time), regardless of the frame rate you’re recording at. With higher frame rates becoming more popular the rules are changing, and the 180-degree shutter actually looks very non-cinematic.

First, you need to understand what a 180° shutter is. Traditional film cameras (for celluloid film) have a rotary shutter—a disc that spins at the same speed (rpm) as the frame rate. So, at 24 fps it spins 24 times per second, and at 48 fps it spins 48 times per second. This disc has an opening, and the size of the opening determines the shutter speed, or exposure time. The larger the opening, the longer the film will be exposed, and the longer moving objects will move during the exposure, introducing motion blur.

“The shutter angle traditionally controls the amount of motion blur. The longer the film is exposed, the more motion blur the image will get.

When the disc is blocking the light, the film is advanced one frame, so the next frame can be exposed. This can be a bit hard for you to visualize, so I made an animation in After Effects that shows how this works.

OK, so now you know what a 180° shutter is, but you might be surprised to hear that you probably don’t have one. Yep, most cameras don’t have one! Instead of spinning discs, digital cameras have electronic shutters, most often reading the image sensor from the top to the bottom. Only very high-end cameras have what’s called a Global Shutter to avoid the dreaded rolling shutter artifacts.

So even if your camera has the option to set the shutter speed by entering a Shutter Angle, you’re really just adjusting the Shutter Speed, measured in time—there is no angle to adjust. The camera menu conveniently calculates the shutter speed based on your shutter angle settings and the frame rate.

Yes, it needs to be calculated, because there is no direct correlation between shutter speed and shutter angle. The shutter speed of a 180° shutter angle is different at every frame rate! Here’s the formula:

Shutter Speed, aka Exposure Time, is defined in seconds, for example 1/48 s, 1/250 s etc. No matter what frame rate you shoot at, you’re always going to get the exact same amount of motion blur with identical Shutter Speed.

Shutter Angle is more complicated, as it gives us a shutter speed that depends on the frame rate that you’re shooting at.

“The shutter angle says absolutely nothing about how much motion blur you get.

I’ll repeat that: The degrees number doesn’t give you any info whatsoever on how much motion blur there is in a frame. None, zip, nada.

Say what? Yes, it’s true. If you shoot 25 fps with an 180° shutter, your shutter speed is 1/50 sec. If you shoot 50 fps with an 180° shutter, your shutter speed is 1/100 second, and you get half the amount of motion blur—at the identical shutter angle setting.

“Motion blur is directly determined by shutter speed, regardless of the recorded frame rate.

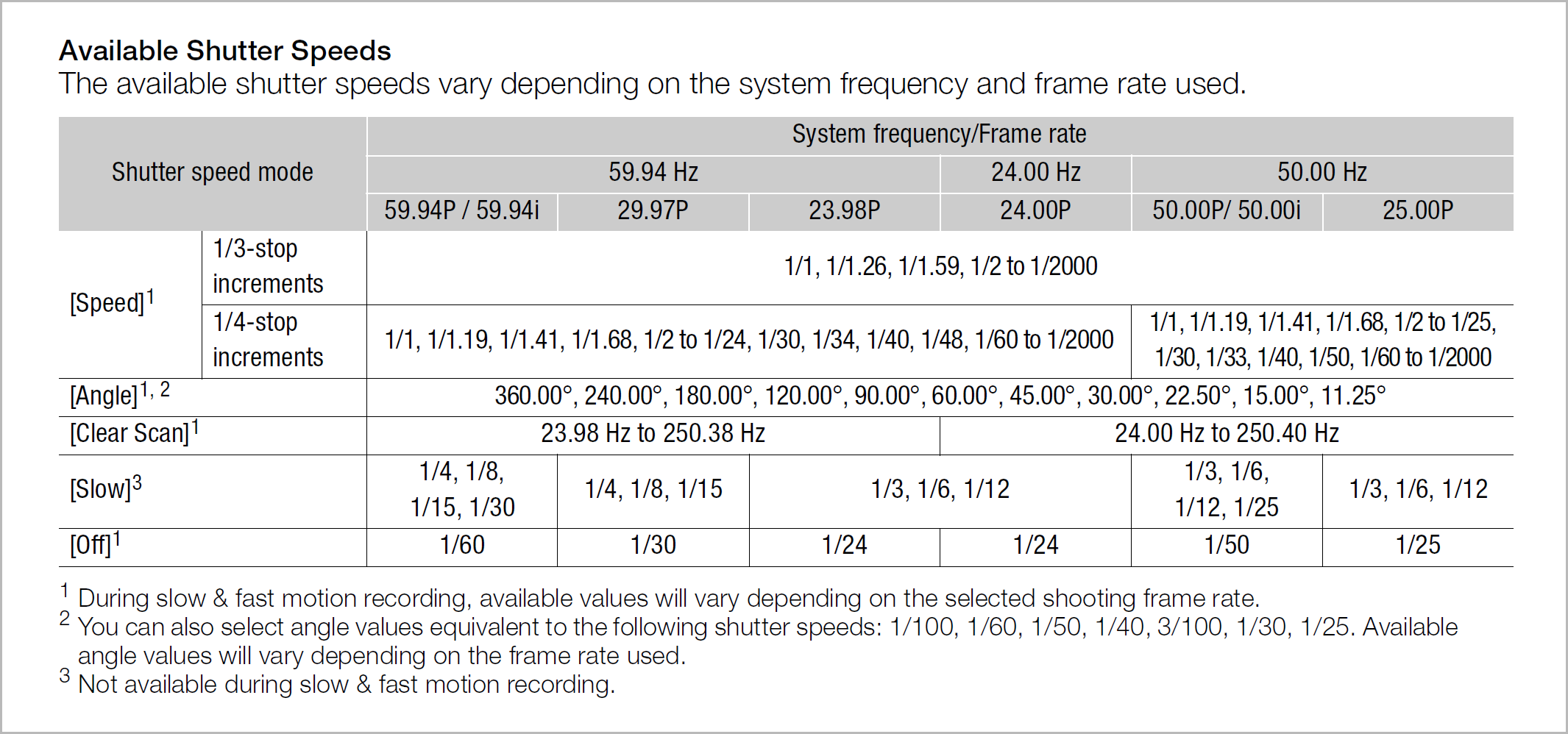

Modern cameras often give you an option to choose between setting the Shutter Speed or the Shutter Angle. Here’s a screen shot from the Canon EOS C300 manual.

An interesting side note is that the C300 manual mentions the Shutter Speed mode “Off”. What would that mean? It means that they set the shutter to 360 degrees. I use this setting when I shoot 50 fps, to get 1/50 second shutter, which is most often what I want. The best thing about this is that the shutter speed can’t be accidentally changed in this mode.

OK, so why do we still measure the shutter speed in degrees? Well, what’s nice about degrees is that it describes the length of exposure as a function of the frame rate. This is very helpful when you’re shooting at higher frame rates to get nice, smooth slow motion. And since films have been viewed at 24 fps in cinemas for almost a century, shooting at higher frame rates has always meant that you were shooting for slow motion.

This is why the 180° shutter rule has become the de facto standard in film making. But now that we have the option to view films at 48, 50, and even 60 fps, the rules have changed, but many industry professionals haven’t been paying attention.

“The 180° shutter rule does not apply when you’re shooting at high frame rates with the intention to show the film at that same high frame rate.

48, 50 and 60 fps for TV is routinely shot with a 360° shutter by many broadcasters. A 360° shutter is impossible on a film camera. That doesn’t mean we can’t use it in a video camera. Since we have an electronic shutter and there’s no film to advance, we can have exposure times as long as the whole duration of a frame.

So at 24 fps we could have shutter speeds up to 1/24 second (360°). You probably don’t want to go that low, but when filming 48 fps for a 48 fps movie, you should definitely use a 1/48 second shutter—which in that case translates to a 360° shutter.

I know, some of you will think I’m crazy, but I’m about to prove why this is true.

Cinematic motion blur means that we get the amount of motion blur that we’re used to see when we watch movies—the amount of motion blur you get with a 1/48 second shutter. We’ve come to accept this as natural looking motion blur—and not surprisingly, it also looks more or less like the motion blur your eyesight has.

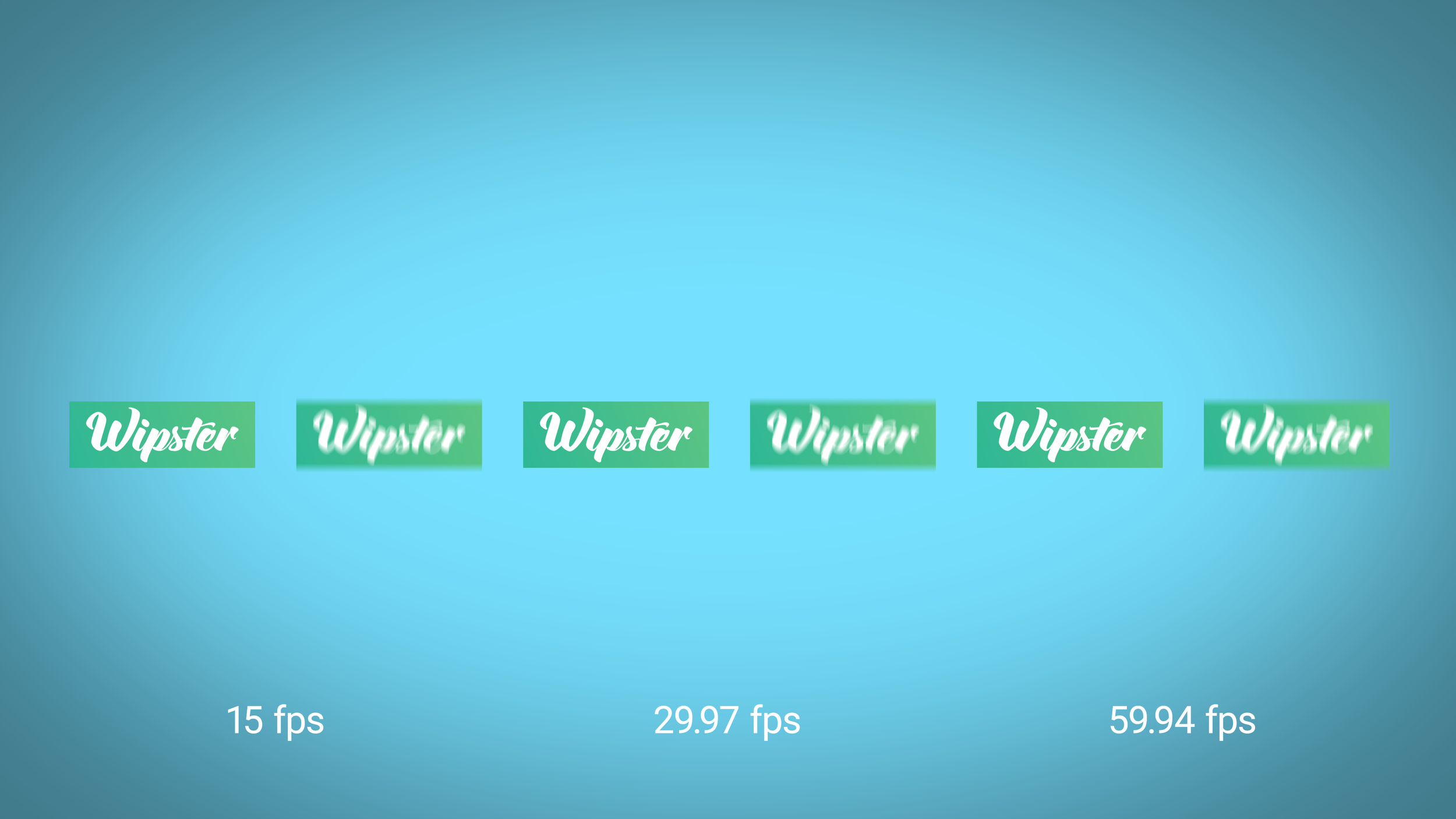

I’ve made an animation that shows the same amount of motion blur for 15, 30 and 60 frames per second. There are two instances of each logo for each frame rate: one with motion blur and one without motion blur.

Since viewing a film on a monitor with the wrong refresh rate will result in stuttery movement, I’ve also made another version that shows 12, 25 and 50 fps. If your screen is set to refresh 50, 59.94 (60) or 100 times per second, at least one of these should be smooth.

FPS Compare 50

FPS Compare 59.94

What can we learn from this? For one, we can see that 12 and 15 fps is not enough to get smooth motion. 25 and 30 is almost enough, but not quite, while 50 and 60 fps both give us perfectly smooth motion (when watched on a 50 or 60 Hz screen).

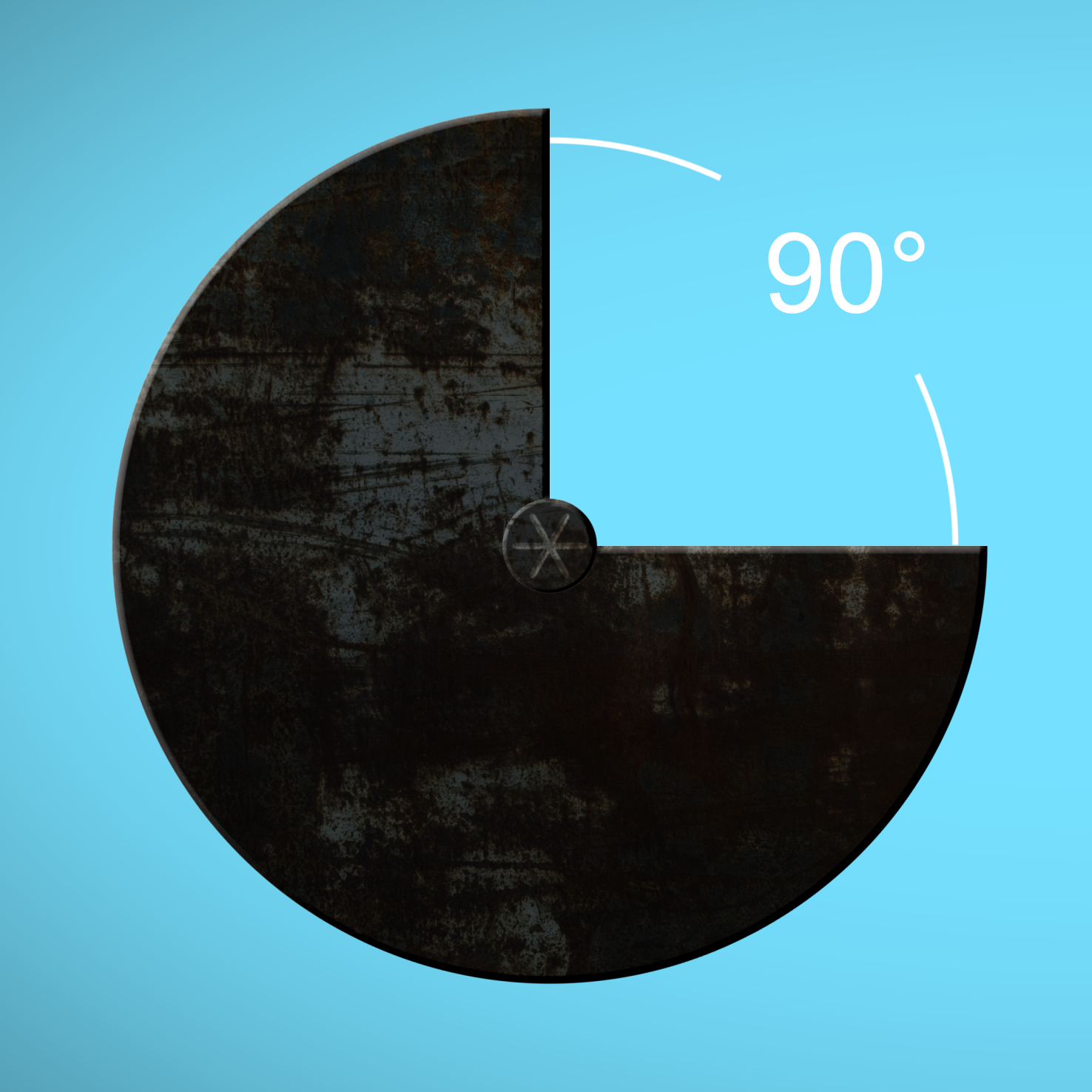

In the image below you can also see that the amount of motion blur is the same on all the ones that has it. To accomplish this, I had to set the shutter angle in After Effects to 90° for the 15 fps precomp, 180° for the 29.97 compo and to 360° for the 59.94 fps precomp. In case you’re wondering: Yes, I did activate the “Preserve fame rate when nested” switch for all of them. So three totally different shutter angles gave us the same amount of motion blur. Because the frame rates were also different, they represent the same Shutter Speed.

Now, still images are not very suited for motion blur comparison. At 1/50 second shutter speed, each frame with moving objects can look bad and blurry, but when you play 25 or 50 such blurry frames per second it’ll look surprisingly natural.

When I see people “explain” why 60 fps films look bad by showing 60 fps video shot at 1/120 second, in a 24 fps YouTube video, I just want to cry. They clearly have absolutely no idea what they’re talking about, because there is no way you can show how 60 fps looks without actually showing 60 frames per second. And why on earth do they change the shutter speed to 1/120 sec?

Yeah, I know. It’s because they believe in the 180° shutter myth.

People don’t seem to understand the difference between shooting at 50 fps or 60 fps for slo-mo purposes in a 24 fps, 25 fps or 30 fps film, and shooting at those frame rates for viewing them at the same frame rate.

This begs the question: Why would you want to make a film at 50 or 60 fps? Because 50 and 60 fps have better temporal resolution, so the footage stutter a lot less than at 24, 25 and 30 fps.

All the movement looks a lot more natural at 50 or 60 fps—but some people claim to absolutely hate the look of 50 or 60 fps. I believe that most of them have never watched 50 fps shot with a 1/50 second shutter on a 50 Hz monitor. I’ve been filming at 50 fps for many years, starting at 720p, but now I shoot 1080p or even 3k and 4k at 50 fps. When people who claim to hate 50 fps watch my films, they don’t even notice that it’s a 50 fps film, because it looks just like 25 fps, but with less stutter whenever there’s movement, so I get smoother panning etc. It has the same amount of motion blur that they’re used to from the cinema.

Want that stutter movement of 25 fps? OK, if I put this 50 fps footage, shot with 1/50 second shutter, in a 25 fps timeline—or export 25 fps video from my 50 fps timeline, there's no difference between this footage and true 25 fps footage. None whatsoever. But movement looks way better when exported as a 50 fps video, of course.

“We must distinguish between shooting at a higher fps for slow motion and for normal motion.

Filmic Pro has a nice way to show this in their framerate settings. They show you both the Capture framerate and the Playback framerate. It’s just adding some metadata to the file, but it’s a nice way to remind the user that those are two very important, and independent, settings.

Why all this talk about motion blur? Because motion blur is important for natural looking motion. Your eyes show motion blur. To experience real-life motion blur, close one eye and wave your hand in front of your face. Does it look more like 1/250 second or 1/48 second shutter to you?

We need a bit of motion blur. Not too much, not too little. Going too far away from 1/48 second will make the motion blur look unnatural, giving you a choppy/stuttery/staccato look and cause a strobe-like effect. It doesn't flow as nicely without motion blur. Instead of feeling like continuous motion, you get the feeling you're watching a bunch of still frames—which, in fact, you are—but the motion blur helps hide this fact, and adds to the illusion of continuous motion.

If you play videogames on a regular basis, you may have become almost immune to the ugliness of no motion blur. Faster GPUs now allow game developers to add motion blur in games too, so maybe the next generation of gamers will not become accustomed to the current hyper-real look of many computer games.

OK, so setting your shutter speed too far away from 1/48 second will make the film look a bit unnatural. Whether or not it looks acceptable is up to you. It’s an artistic choice. But please don’t let your frame rate dictate what shutter speed you should use. There’s no reason that 50 fps footage should have a different amount of motion blur than 25 fps footage.

There’s no way to convey with text exactly how the different shutter speeds and frame rates look. So let’s watch some video instead. Here are some examples to feast your eyes on, recorded on my request for this article by Jens Petter Larsen at Refleksfilm.

Note that the motion blur will be significantly different at different points on the wheel, from the hub to the tire.

Motion Blur Test 24 fps

Motion Blur Test 25 fps

Motion Blur Test 29.97 fps

Motion Blur Test 50 fps

Motion Blur Test 59.94

Of course, rules are meant to be broken. You can use long or short shutter speeds, fast or slow frame rates, whichever best complements your stories. Yes, there are several good reasons for not using a 1/48 second shutter speed.

The most obvious one is if you’re shooting for slo-mo. If you’re shooting 50 fps to use it as slo-mo in a 25 fps sequence, go ahead and shoot with a 1/100 second shutter (180°). Shooting at 1/50 second (360°) for slo-mo will result in too much motion blur to look natural. It may be a cool effect, but it will not look natural.

“We must distinguish between shooting at a higher fps for slow motion and for normal motion.

The shutter speed should normally not be used for controlling exposure. We use the iris, ISO and ND filters, for controlling exposure. But since shutter speed affects motion blur and exposure, you can adjust shutter speed, within reason, to accommodate exposure issues. An interview with very little movement may look totally OK with a faster shutter speed, and if you don’t have an ND filter at hand, it may be a good way to get the right exposure.

Motion blur can cause problems for green screen keying. You can shoot green screen footage at higher shutter speeds to avoid motion blur, and then add motion blur to the finished composite to make it look natural.

“Motion blur can also cause problems for tracking, rotoscoping, stabilizing etc.

The algorithms will struggle to find the pixels they’re looking for when there’s too much blur. You can use a fast shutter speed to make the warp stabilizer in Premiere Pro work better, and then add motion blur to the stabilized footage with plug-ins like ReelSmart MotionBlur, Twixtor or just use CC Force Motion Blur in After Effects. Getting really good results from adding motion blur in post can be hard. You can get smearing artifacts on complex motion, especially with several layers of moving objects. But often, depending on the complexity of the footage, it can look quite convincing.

If you’re shooting 25 or 50 fps in a country with 60Hz lighting, and the scene is lit by electric lights you will often get rolling dark lines in the footage if you use a 1/50 second shutter. In that case, set the shutter to 1/60 second to avoid problems. You can get the same problems with HMI lights and sodium or mercury vapor lights, but those are less common.

If you experience rolling bands or other problems when shooting a computer screen, make sure you get the shutter speed in sync with the scan lines or refresh rate of the screen.

You can use faster shutter speeds to create an uneasy feeling. Or use it for artistic purposes if you want. If you shoot and play back at 60 fps (not unusual at sporting events, like tennis matches), you can shoot at a faster shutter speed just to be able to see the ball better. It will not look as natural, but it may look better. If you’re filming something larger than a tennis ball you probably don’t want to do this, as the motion blur at 1/60 second shutter speed looks more natural than at 1/120 second.

Shooting at longer shutter speeds has fewer practical purposes, but you can use a 1/6 second shutter to create a dreamy, artsy look. When you shoot at 1/6 second in 24 fps, the camera will duplicate frames, so you get an effective 6 frames per second, each frame recorded four times.

You can use alternate shutter speeds for improved storytelling. There are many examples of film makers using the shutter speed to help tell the story. Let’s have a look at a few of them.

Faster shutter speeds are often seen in action sequences. The footage can feel too sharp—so sharp it can be uncomfortable to watch, but the viewers may not know exactly why they have this feeling.

The most commony referred to example of fast shutter speeds is the invasion scene (the beach storming at Normandy) at the beginning of Saving Private Ryan.

In the infamous D-Day scenes in the 1998 movie Saving Private Ryan, Steven Spielberg and cinematographer Janusz Kaminski used both 90° and 45° (1/96 second and 1/192 second, respectively) shutters to make the scenes more frightening and hyper-real, more like the way the soldiers experienced the horrors on the beach.

Whenever there’s an explosion (and there are a lot of them) you can see the dirt and individual pebbles of debris from an exploding mortar.

“Often, when you see an explosion with a 180-degree shutter it can be a thing of beauty, but a 45-degree shutter looks very frightening. … I used a 45-degree shutter on the explosions, and a 90-degree shutter on most of the running shots. But we alternated at times. Sometimes the 45-degree shutter would appear too exaggerated and the 90 turned out to be better. But for extreme explosions like this, where we really wanted to practically count each individual particle flying through the air, the 45-degree shutter worked best.” – Steven Spielberg

They even lowered the frame rate a few times as well, to be able to use very long exposure times, to give a disoriented feel.

“Even though Saving Private Ryan has become famous for the use of fast shutter speeds in this scene, the majority of the scenes were shot with the standard 1/48 second (180°) shutter speed.

I recommend reading Jeffrey Ressner’s interview with Steven Spielberg in the article “War is Hell” on the web pages of the Directors Guild of America.

Films like Gladiator, 25th Hour, and 300 have also used fast shutter speeds to create a distinct look in their fight scenes. The movie 28 Days Later explored the same technique to make the zombies look unreal.

The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey got 48 fps a bad reputation. When it was released, people were saying “48 fps looks awful”. What they really saw and hated was a fast shutter speed (and too much depth of field). The Hobbit did much more than 48 fps. They also did 1/64 sec (270°) shutter, and used small apertures because they wanted a huge depth of field. A fast shutter and a small aperture meant that they needed a lot of light. That harsh lighting in the indoor scenes reveals the make-up, and due to the huge depth of field we can see details in the sets which look like it’s made from Papier-mâché or polystyrene.

Especially strange was a scene where CG wolves had natural motion blur, and the landscape they were comped into did not.

The Hobbit gave 48 fps a bad reputation because they didn't use the normal cinematic standards like a 1/48 second shutter, and large apertures to facilitate motion blur and bokeh.

Jackson did learn from his mistakes, and admitted to spending a lot of time softening parts of the image in post on the last two Hobbit movies: "When I did the colour timing this year, the colour grading, I spent a lot of time experimenting with ways we could soften the image and make it look a bit more filmic.”

In one episode of Homeland, CIA agent Carrie Mathison gets bad medicine. She’s got a bipolar disorder and is normally on mood stabilizers to avoid becoming manic. In this episode, the enemy switches her medicine, which causes a major manic event. They used both slow and fast shutter speeds to augment our experience of Carrie’s attack.

When we’re watching Carrie from a distance, they use a normal shutter speed, and when we’re experiencing the scene through her eyes, they use fast and slow shutter speeds. This gives us an uncanny feeling that there’s something wrong.

The gist of this article is really simple: Whenever possible, shoot at 1/48, 1/50 or 1/60 second shutter speed unless you have a good reason not to (as you’ve seen, there are some very good reasons that may apply). If you’re shooting higher frame rates with the intention of slowing down the footage to 24 or 25 fps in post, by all means use the 180° shutter rule.

If you’re not sure how the footage will be used it’s probably best to shoot at faster shutter speed, rather than slower. It’s possible to add somewhat real looking motion blur in post, but it’s really hard (often impossible) to remove motion blur once it’s captured.

Next time you end up in a discussion about shutter speeds and shutter angles, point them to this article and make them watch the video examples. A little warning, though: Some people will continue to argue that the 180° shutter rule is always valid. Please don’t argue with them. Instead, use the info here to shoot footage with good looking motion blur, and let them be the ones to deliver inferior quality.

If you're a new user of Wipster or have just missed some of our recent updates, you might have missed some things:--Wipster's suite of integrations...

We’re excited to announce a powerful new integration that brings Wipster’s intuitive video review tools directly into Final Cut Pro (FCP). Designed ...

1 min read